The Last Man

Who Knew Everything

A Biography of Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680), a German Jesuit scholar known for his prolific writing in areas of linguistics, natural philosophy, and theology among many other topics, was a man well regarded by his peers and a man of faith. His writings detailing his studies and experiments were prolific but by his death in 1680, many of them were antiquated by the rise of rationalism and the Enlightenment.[1] Born in Geisa, Germany in either 1602 or 1601 to a professor of theology, he was interested in both academia and joining the Catholic church at a young age. By 1612 Kircher was accepted by the Jesuit school in Fulda and began studying at the seminary school there until 1616 when he applied to join the order officially in Mainz, his religious nature already developing as a teenager. He underwent the two-year initiation period in Paderborn, where he and the other novices adhered to a strict routine of prayer, meditation, and self-denial, with supplementary studies in philosophy and theology. However, his studies were disrupted by the Thirty Years War and the insurgent Protestant forces and uprisings forcing the initiates to flee to Cologne.

In Cologne, Kircher was able to study physics and natural science before being sent to teach Greek at the College in Coblenz in 1622. In 1623, he was sent to Heilingenstadt to teach Latin, finally finding himself with the time to pursue his own personal studies. At the end of 1624, he returned to Mainz to prepare for his ordination into the priesthood. This preparation included four years of studying theology and oriental languages in the hopes of being sent to do missionary work in China. In 1628, he spent a year of his studies in Speier before being sent to the college in Würzburg where he taught moral philosophy, mathematics, and Hebrew. The medical school attached to the college there possibly inspired Kircher to pursue his own interest in medicine. It was also here that he published his first book, Ars Magnesia (1631). However, shortly after its publication, Protestant armies invaded again, forcing the college to flee. In short order, they fled to Mainz then Speier, and were finally forced out of Germany all together, where Kircher traveled to Lyon, and then quickly oto Avignon in France.[2]

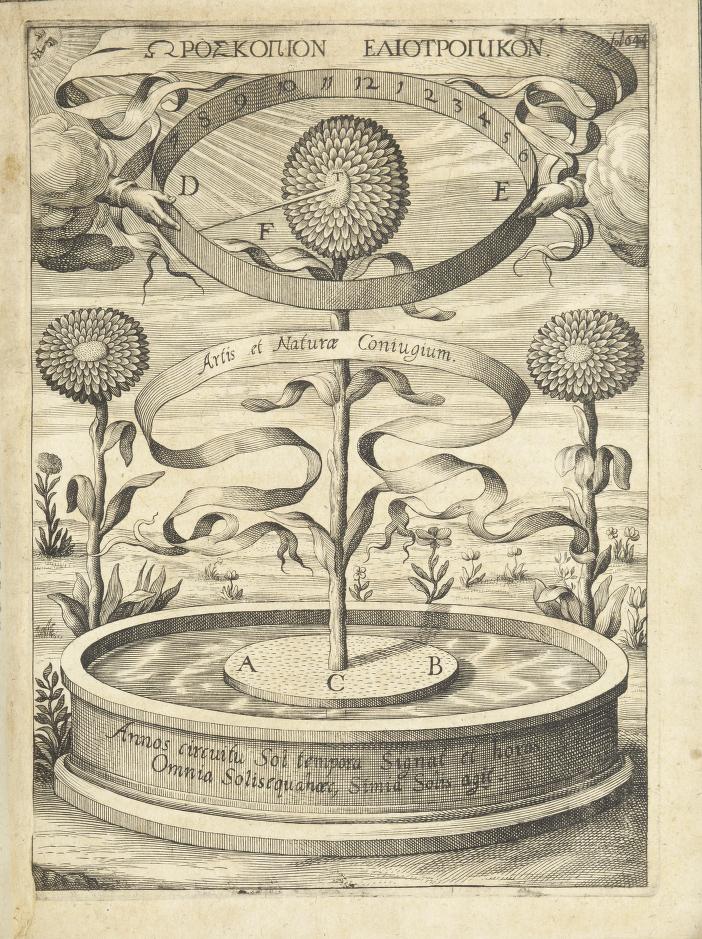

Kircher would remain in Avignon for two years where he would develop his sunflower clock, as described later in this paper. In 1632, Kircher was appointed to the court of Emperor Ferdinand II in Vienna, but ultimately was redirected to Rome and the papal courts under Pope Urban VIII. He would not reach the city which would prove to be his final home until 1634. Early in his career he taught at the Collegium Romanum, covering both Hebrew and mathematics.

His knowledge of oriental languages was of interest to his colleagues, and he published a book on Coptic, Podromus Coptus Sive Aegyptiacus in 1636. In 1638, Kircher took several trips away from Rome on Jesuit business, one months long trip to Malta, and another of similar length to Syracuse and Sicily. Both journeys inspired further studies in the natural sciences, especially with his observations of earthquakes in Calabria. It was during this time that he was able to visit Mt. Etna, and even observe the inside of the caldera. However, once he returned to Rome, he would not leave for any significant amount of time again. [3]

Kircher’s return marked the beginning of his major investigations into the field of natural philosophy, with Magnes, sive de Arte Magnetica published for the first time in 1641, and two other great works on topics in the natural sciences, Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae (1646) and Musurgia Universalis (1650) following close behind. With the exception of Mundus Subterraneus (1664), after these first three large works were published, most of Kircher’s work following these focused on topics of linguistics, cryptology, and theology with smaller investigations into natural phenomena sprinkled throughout.

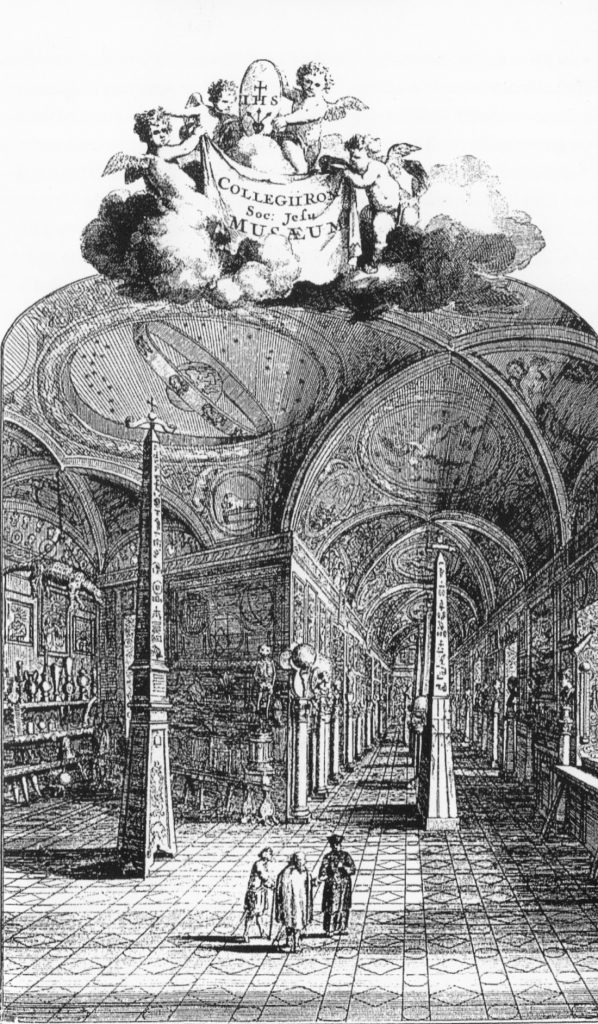

By 1645, Kircher was no longer required to teach, and instead pursued his own studies, as well as taking custodianship of the museum in the college, where Kircher was able to exhibit his own personal collection of devices and inventions. By 1650, Kircher was well established both as a Jesuit and in the field of academics, and the next few decades of his life would be devoted to the museum and religious duties, his writing and studies, and correspondences with other scholars.

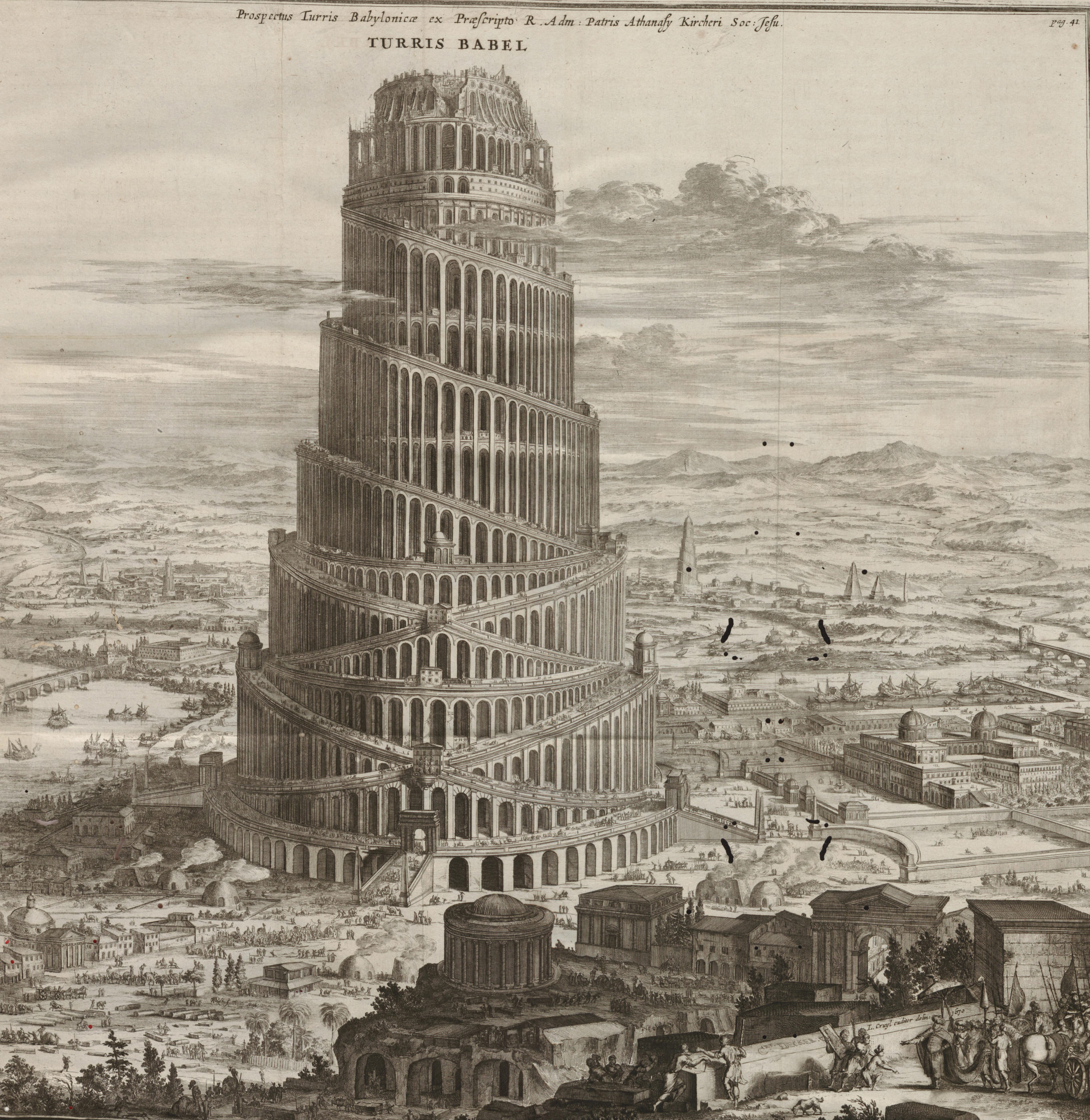

In the final decade of his life, his publishing focus shifted to religious works, writing books on both the tower of Babel (Turris Babel, 1679, Amsterdam) and Noah’s Arc (Arca Noë, 1675, Amsterdam). He remained active in correspondence, but eventually passed in 1680, coincidentally the same night as sculpture Lorenzo Bernini. In 1684, Vita was published with a selection of his correspondences and his autobiography, written before his death.[4] Kircher’s early life was marked by his piety and fervent interest in academics, while his home was beset by instability due to the sectarian conflicts of the Thirty Years War. However, he was eventually able to find consistency in Rome, as he established himself as an academic. He wrote prolifically, on a wide variety of topics. However, Kircher’s work, as well as its reception, was no doubt influenced by the ideological change from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment. He was, through his faith and scientific interest, positioned between the church’s ideology and the new secular – and occasionally heretical – path scientific theory and discovery was taking.

[1] Martha R. Baldwin, “Athanasius Kircher and the Magnetic Philosophy” (PhD diss., University of Chicago, 1987), 3-9.

[2] John Fletcher. A Study of the Life and Works of Athanasius Kircher, ‘Germanus Incredibilis:’ With a Selection of his Unpublished Correspondence and an Annotated Translation of his Autobiography, ed. Elizabeth Fletcher (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2011), 5, 13.

[3] Fletcher, A Study of the Life, 15-30.

[4] Ibid., 31-66.