A Compendium of Knowledge

On Magnetism

| Title | Magnes, siue, De arte magnetica opus tripartitum […] |

| Author | Kircher, Athanasius (1602-1680) |

| Year | 1643 |

| Place | Cologne |

| Contributor(s) | Kalckhoven, Jost (-1669) – printer |

| Physical Description | Signatures: *, **, [pilcrow]⁴, 2 [pilcrow]², A-5M⁴ 5N² ; Bibliothèque de la Compagnie de Jésus ; Headpiece; tailpieces; initials ; Printed on different weights of paper ; Includes index ; Burns Library copy: engraved bookplate on front pastedown: Friederici Nicolai et amicorum ; Burns Library copy: bound in vellum over boards |

| Collection | Boston College Libraries |

| Source | Internet Archive (public domain) |

Magnes sive de Arte Magnetica (1643)

Structure & Organization

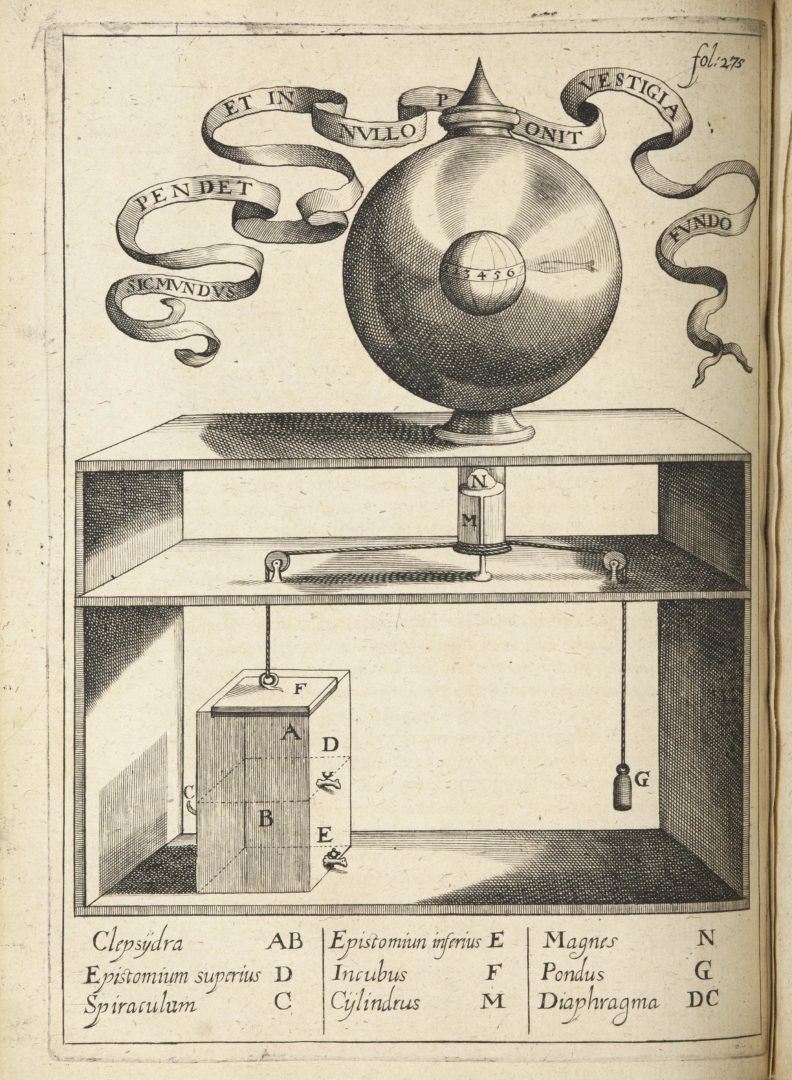

Magnes is separated into three books.The first is called Artis Magneticae, De Natura et Facultatibus Magnetis (Of the Nature of and Applications of Magnets) where Kircher introduces the idea of a magnet and how it acts mainly through theorems and proofs. The entries tend to be shorter, with explanatory diagrams and matter of fact explanations. The second book is Magnes Applicatus, Quo varius huius lapidist usus declarator (Where the Various Uses of This Stone Are Declared). In this book, Kircher delves into the applications of magnetism, introducing more contemporary questions around magnetism, and demonstrating how one can use the theorems from the previous book to solve questions and problems of the natural world. The third book, Artis Magneticae Mundus sive catena magnetica (The World or the Magnetic Chains) deals with the more esoteric topics, the applications of magnetism not applicable to the loadstone or the Earth’s magnetic field. While he does talk about mineral magnetism, the general theme of this book is more theoretical, rather than the clear applicable diagrams and problems of the previous two books.

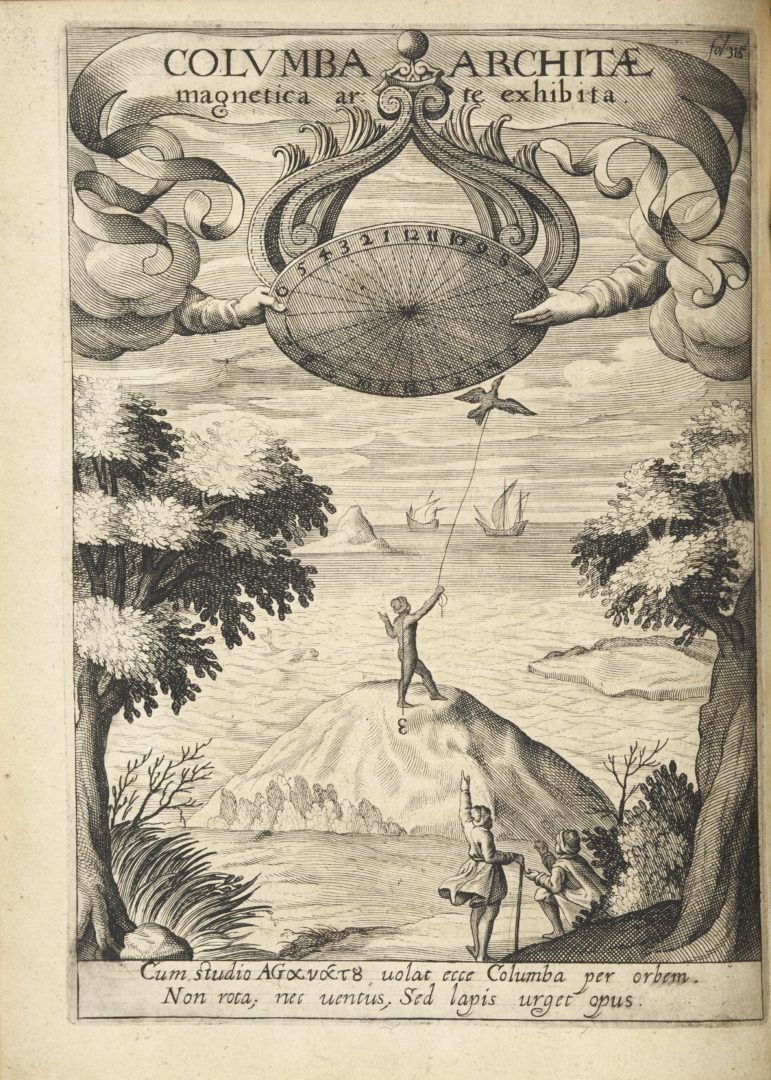

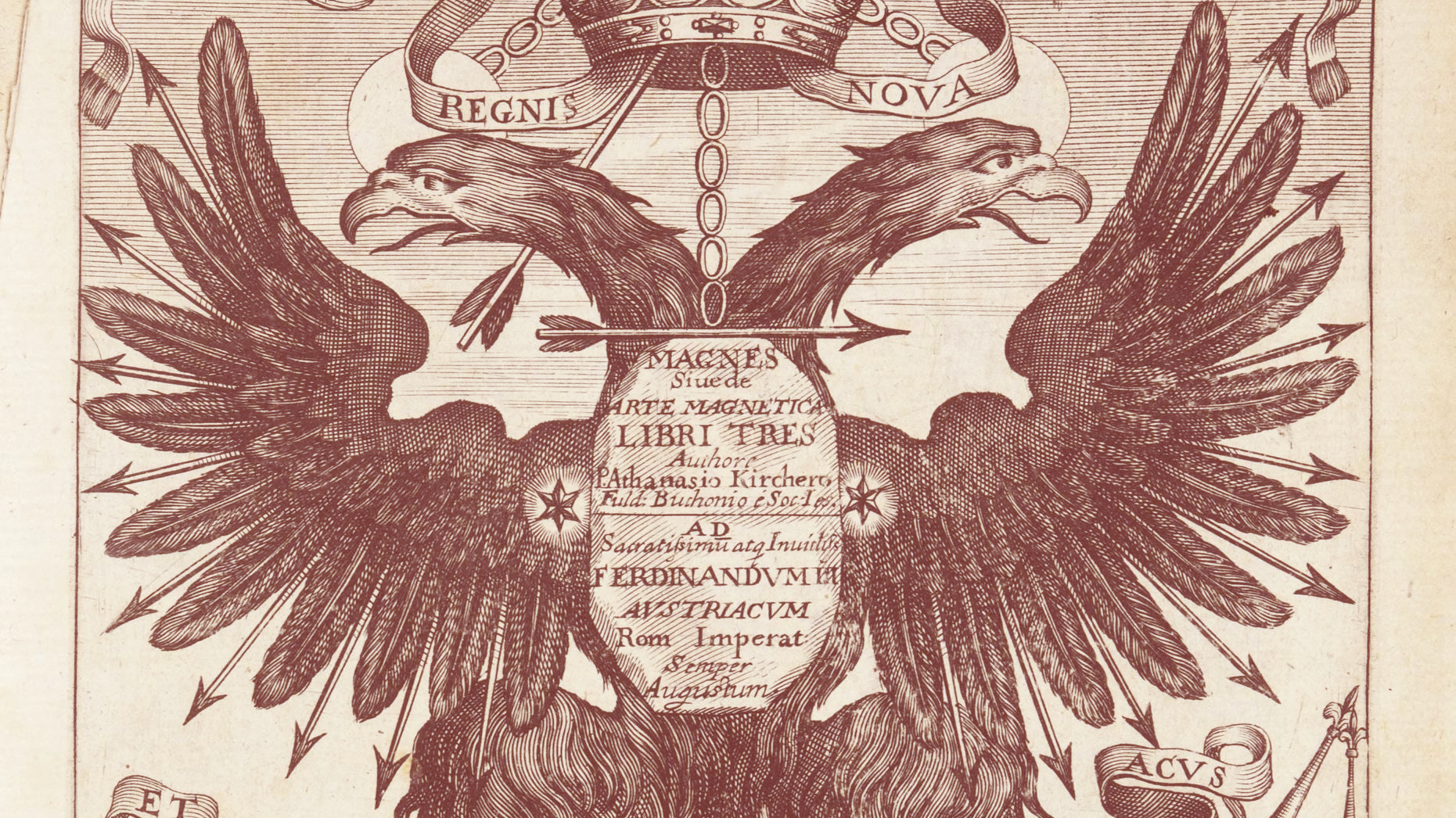

The book begins with an engraving of what has been termed the magnetic Hapsburg eagle, where the double-headed eagle and crest of the Hapsburg empire is heavily embellished with arrows or compass needles, and a pun utilizing an allusion to the north and south pointing needle of a compass with the similarity between the word austri and the Austria of the Hapsburgs. The image also includes the eye of God looking down on the scene, with cities and the Earth at the bottom. It is both a dedication to a powerful family and a visual metaphor for the pervasiveness of Kircher’s magnetism. There is similar magnetic imagery included throughout these preface pages, with both a compass and a loadstone making appearances. Throughout the preface, Kircher includes quotes and musings on the nature of magnetism before delving into the more technical aspects of book one.[1]

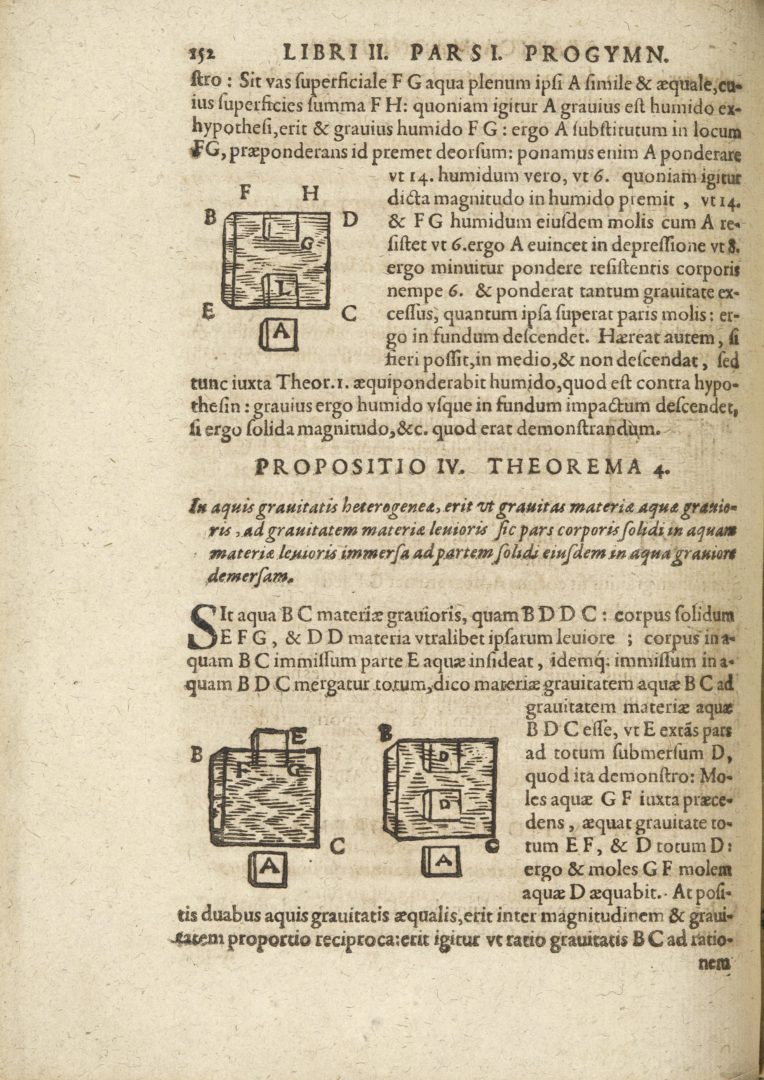

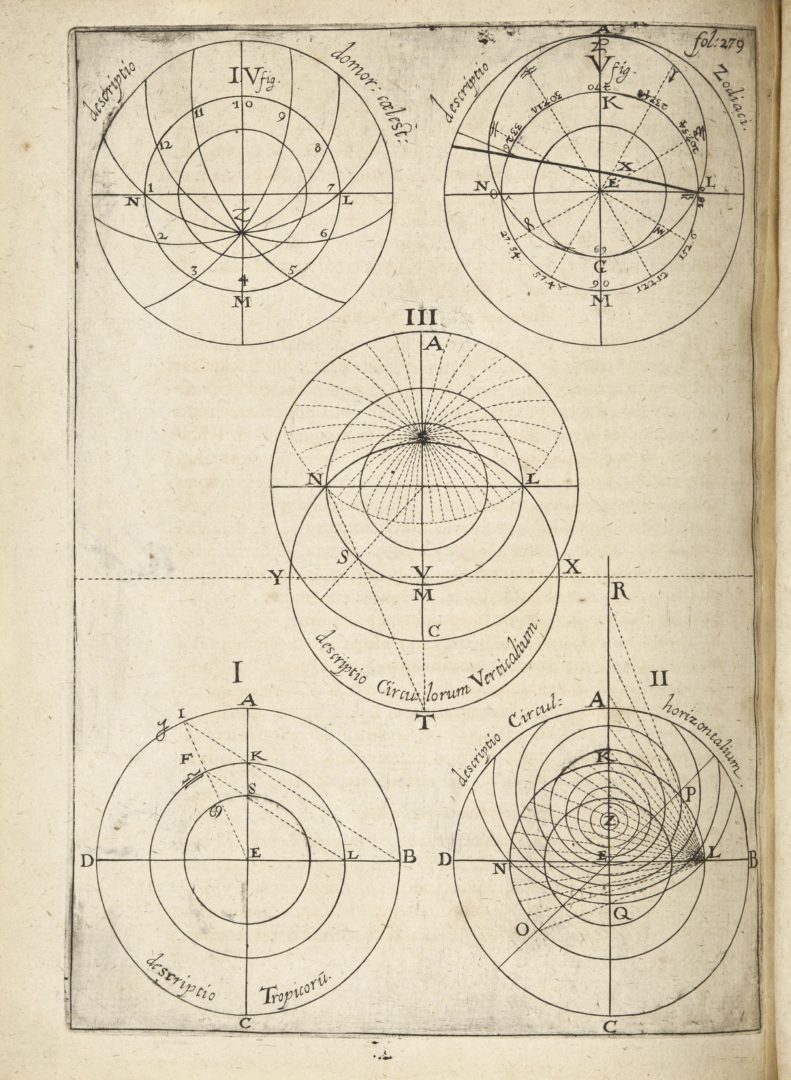

Kircher begins book one with a discussion of previous works on magnetism, drawing from Greek, Latin, and Hebrew writings. He then summarizes the various topics which will be later discussed in greater depth, before moving into the instructional section of this book. He begins by defining the effects of a magnet in twenty individual rules, each dedicated to a different element of the attraction and repulsion force of a magnet, the loadstones ability to move iron, and the polar nature of a magnetic field. After setting these rules, he then begins to explain them in more detail, through various theorems and diagrams. Kircher did not use many equations in his work, but often relied on geometric explanations and proofs. He also described many of his experiments, which he would rely on in later arguments.[2]

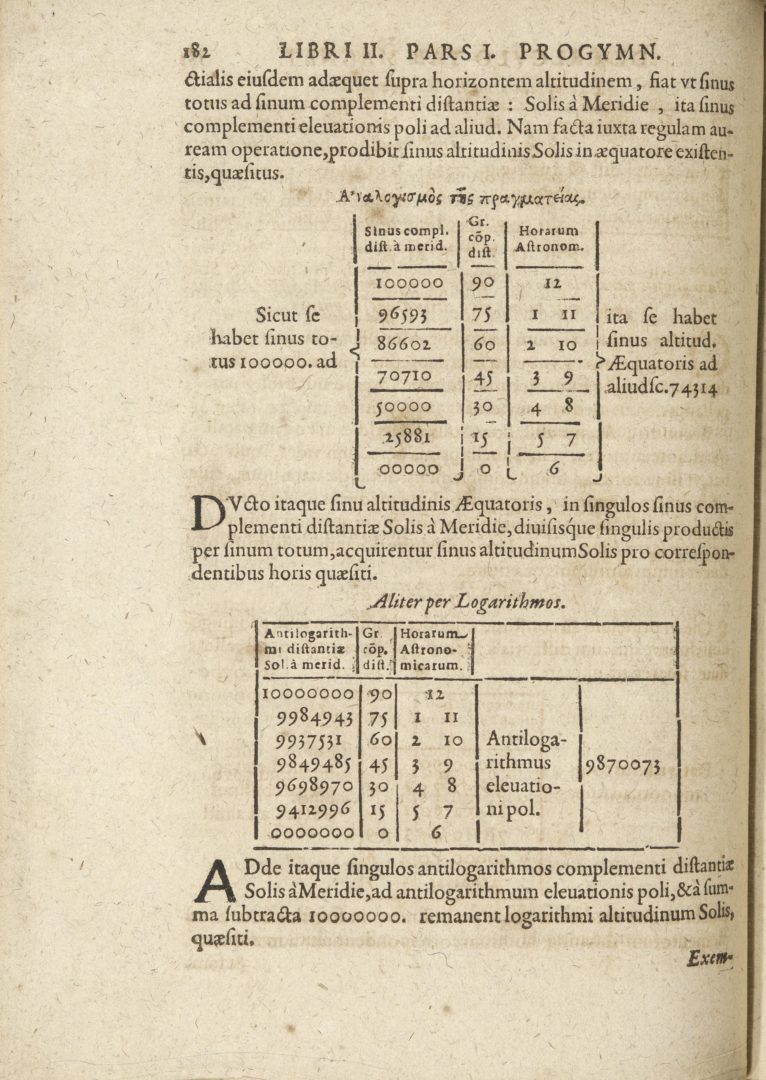

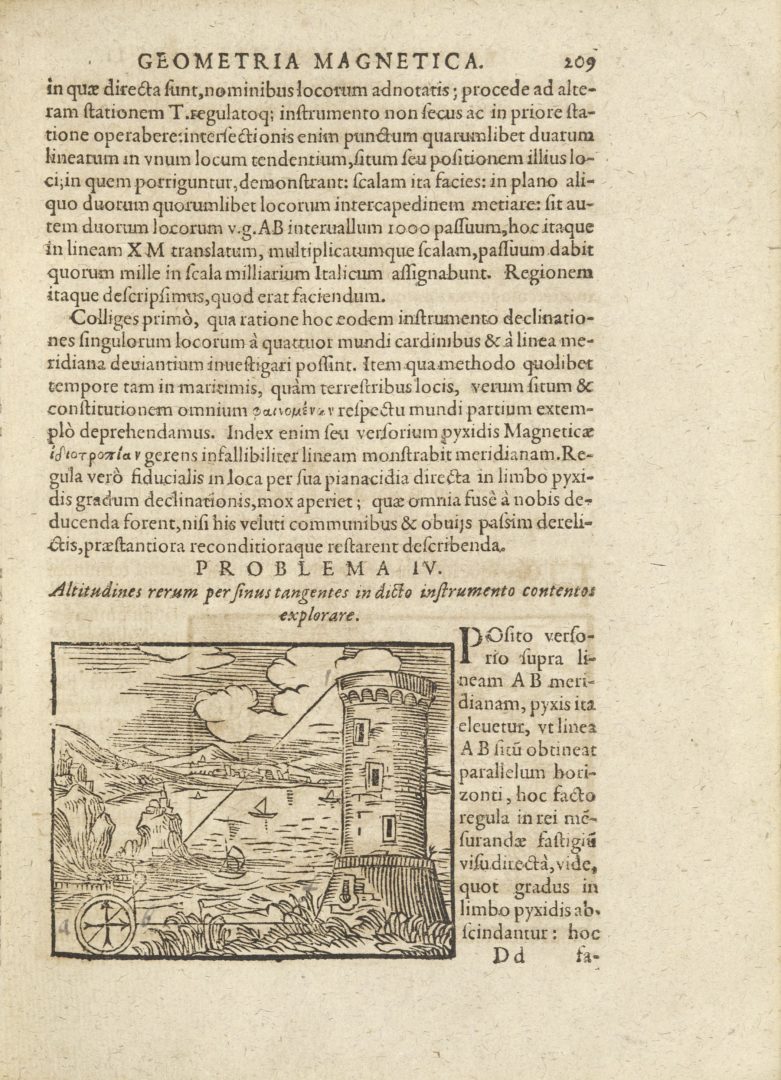

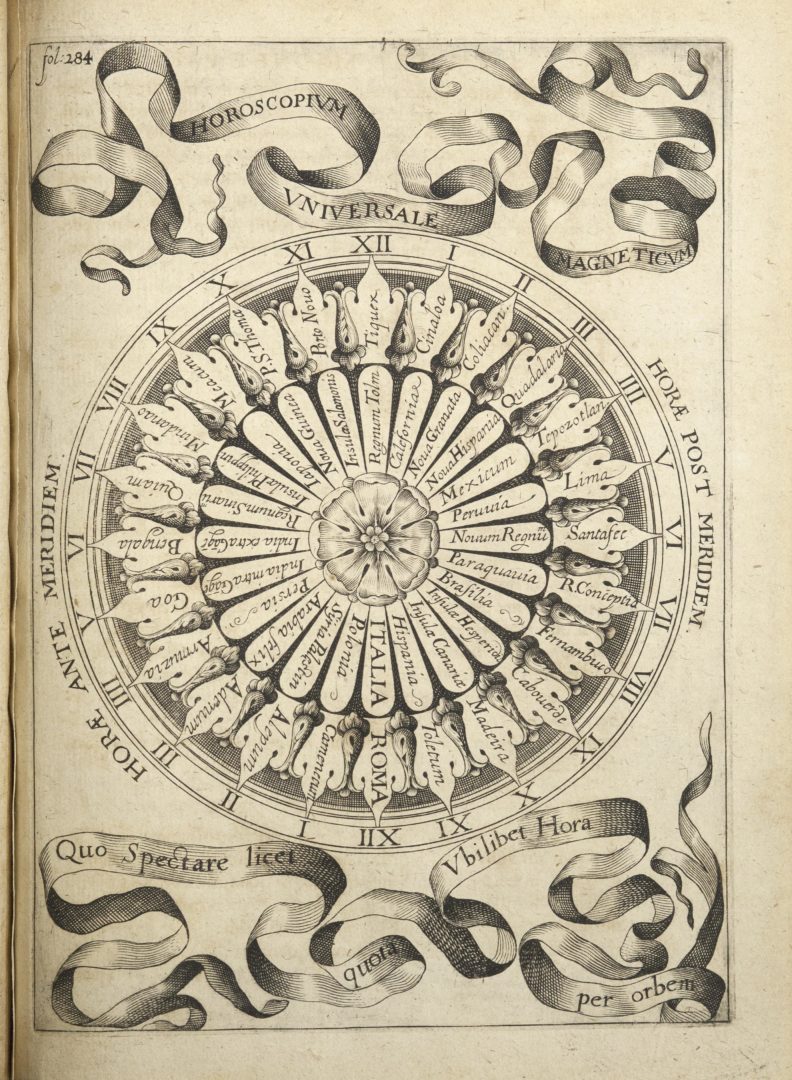

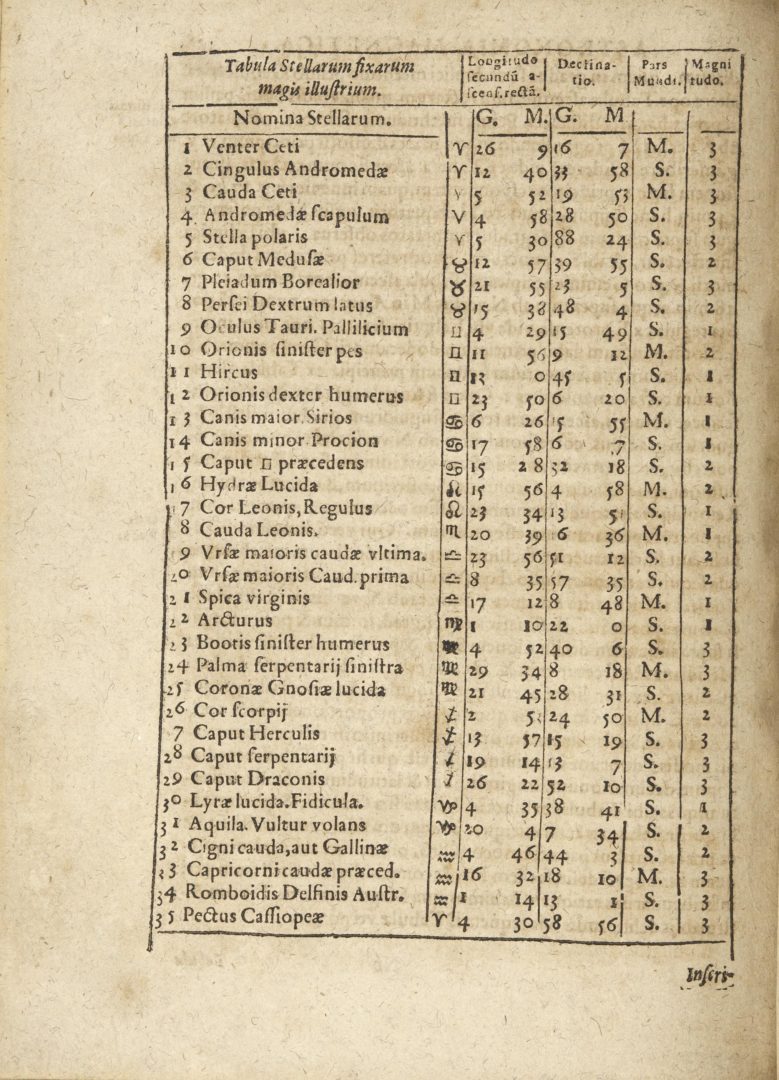

The second book deals with more theoretical questions, writing on topics without established and accepted answers. He poses more problems without a real-life analogue, or explores recently discovered issues, such as the magnetic dip and variation which will be discussed later in the paper. Kircher has more detailed diagrams and schematics, which he seems to be relying on not as a visual aid to a common place idea, but rather as scientific proof and explanation of a new or difficult concept. In addition to these detailed diagrams, he includes charts of data and measurements. There is much more scientific experimentation occurring in this book. The illustrations in this section vary between diagram and artistic depiction of magnetic concept, with carefully measured globes interspersed with angelic hands holding esoteric symbols.[3]

In the final book, Kircher becomes more creative in his application of magnetism. His diagrams of machines and inventions are less detailed and more fanciful, with much more writing. His chapters are denser, and the topics are more expansive. It is in this section that most of Kircher’s writing on topics outside of the modern understanding of magnetism occur, such as his botanic and medical magnetism. It is also in this section where Kircher’s main refutation of Kepler and heliocentrism occur. Kircher concludes his book with a theological discussion of the magnet and God. This will be later discussed, but it commands an entire chapter, the final piece of the book for the reader. It is meant to tie all of the long and varied discussions of magnetism into scripture and God. While Christian concepts are present throughout the book, he makes the connection explicit at the end.[4]

[1] Athanasius Kircher, Magnes Sive De Arte Magnetica Opus Tripartitum, 3rd ed. (Rome: B. Deversin, 1654), https://archive.org/details/KircherMagnesSive1654, 5-22.

[2] Ibid., 1-112.

[3] Ibid., 113-375.

[4] Ibid., 376-613.