Magnetismus Planetarum

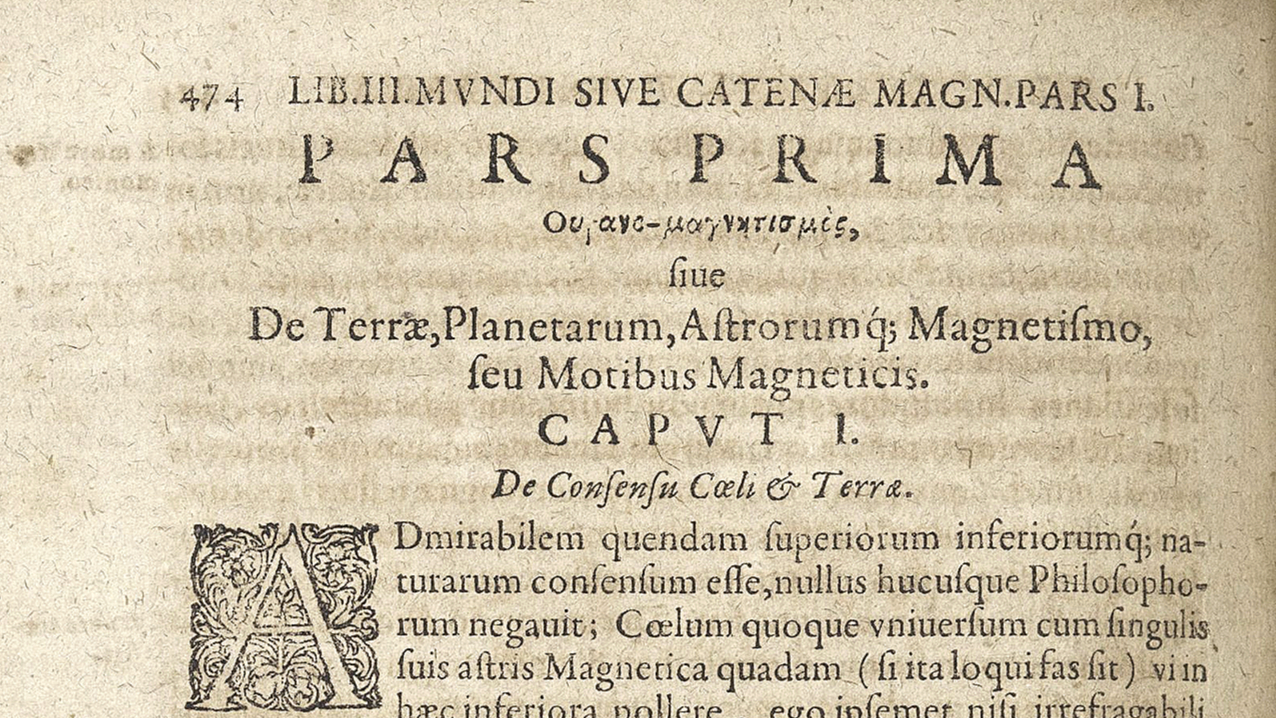

The First Part of The Third Book of The World or The Magnetic Chains: Of the Earth, of the Planets, of the Stars; Magnetism, or Magnetic Movements.

Kircher’s

Magnetismus Planetarum

Chapter on Planetary Magnetism from Magnes sive de Arte Magnetica (1643)

Attributed to Boston College Libraries, public domain, via Internet Archive

Magnes was not just a work for Kircher to expound upon his magnetic theories, but to create a precise reference work for any magnetic matters; this necessitated not just his own theories and experiments, but correcting misconceptions and erroneous conclusions about the nature of magnetism. Nowhere is that more apparent than in his writings on astronomy, wherein he offers no new theory or topic but rather focuses on rebutting the usage and application of magnetism by heliocentric authors, namely Johannes Kepler and Gilbert. This section, differs quite significantly from his other topics. Kircher devoted most of his attention to disproving claims of magnetism in heliocentric cosmology. This was the first Jesuit affiliated scientific refutation of Copernican argument to be published, and accordingly Kircher took it seriously, applying not only scientific but religious arguments as well. [1] While his other sections developed the scope and applications of magnetism, no other topic was as mired in public controversy and scrutiny, especially as a Jesuit scholar who was installed at the offices in Rome, the seat of papal power. It was necessary for his section to be clear, precise, and demonstrate the flaws Kircher found in the arguments of the heliocentrists.

As followers of Copernicus abandoned traditional cosmology, they found themselves searching for new theories as to how the heavens worked, as the traditional Aristotelian concepts of fixed perfect bodies could no longer coexist with the new path astronomy was taking. The orbits of planets and stars were perplexing, and many turned to magnetism as a way to explain this. Notably, Kepler believed, through his extensive studies of the orbits of planets and asteroids, that it was through magnetism that these orbits existed. Similarly, the rotation of the Earth was attributed to magnetism as well, where it was turned through its attraction to the sun. Gilbert went further and assigned ferrous properties to the moon, which connected it to the Earth. Kircher argued these claims were incorrectly applying magnetic theory and would, generally, result in catastrophic collisions between the various heavenly bodies and the Earth. He first denied that there was any experimental basis for cosmic determinations. It could be observed that a sphere in the center of the universe – as defined by geocentrists – moved differently from a sphere on the edge of it. Additionally, he disagreed with the argument of the Earth being magnetic, instead likening it to a material which had magnetic properties, such as iron, but was not a loadstone. If the Earth was a magnet, Kircher argued, all iron on earth would be attracted to a single point and it would be an un-usable material. In response to Gilbert’s theory of the moon, Kircher scathingly referred to it as absurd, undignified, and intolerable, saying that if Gilbert’s supposition was true then the Earth and the moon would crash into each other. Similarly, as he turned his view to Kepler’s theories, he questioned what kept the planets from bumping into each other. He also found a contradiction in the logic – what fixed the stars in place, but allowed the planets to move, and to move in imperfect elliptical orbits? Furthermore, he extrapolated from magnetic properties that there was no way for a spinning magnet to move another magnet in a circle around itself. Kircher, in his scientific argument, focused primarily on this issue of magnetic attraction between the heavenly bodies, but it was a significant problem in the Copernican cosmos, one which would be solved with the discovery and development of the theory of gravity. [2]

Kircher’s scientific arguments were not made solely for the sake of scientific integrity, but to protect the religious integrity of the word of God and the church. He emphasized the arrogance of Copernican astronomers, who valued the word of man over scripture. This strong condemnation of a lack of scriptural attention was threaded through the text of the scientific theory. Kircher did believe, very deeply, in the inherent truth of scripture, that all things could be related and discerned from the word of the Bible. However, this specific argument followed very closely with the official position of the Catholic church. As will be discussed later, Kircher did not always directly follow said official position, but in this specific section his writing is very closely aligned with the church and inquisitorial positions. [3]

One of the important elements of Kircher’s cosmology and magnetism, beyond the commentary on the Copernican arguments, was the distinction made between heavenly and terrestrial bodies. This is an old distinction, and fully in line with Aristotelian cosmology, but it does clearly delineate magnetism as a terrestrial force, rather than a celestial one. This sets Kircher apart from other scholars of the day, many of whom believed in a celestial origin for magnetism. To Kircher, magnetism was a terrestrial force, one which pervaded all elements of terrestrial existence, even if its influence in the heavens was less evident.

[1]

Martha Baldwin, “Magnetism and the Anti-Copernican Polemic,” Journal for the History of Astronomy, no. 16 (1985), 158-160, 1985JHA….16..155B Page 158 (harvard.edu).

[2]

Martha R. Baldwin, “Athanasius Kircher and the Magnetic Philosophy” (PhD diss., University of Chicago, 1987), 214, 217-218, 273-279.

[3]

Baldwin, “Magnetism and the Anti-Copernican Polemic”, 160-162.