Magnes Epilogus

The Tenth Part of The Third Book of The Magnetic World: Magnes Epilogue, that is, God, the most good, the greatest magnet of all nature

Kircher’s

Magnes Epilogus

Epilogue on the Theology of Magnetism from Magnes sive de Arte Magnetica (1643)

Attributed to Boston College Libraries, public domain, via Internet Archive

Kircher’s final chapter of Magnes is more theological discussion than scientific inquiry; it is the full culmination of his system of magnetism, bringing this force which impacts all elements of terrestrial life and expanding the analogy to God and Christianity. Kircher’s concept of God was that God was the central magnet of the universe. In the previous sections, Kircher had established the breadth of the influence of magnetism upon the natural world and brought his book to a full conclusion by drawing the connection to this power and the hand of God in it. The book itself is structured beginning with the small fundamental understandings of magnetism, and slowly expanding and widening the scope and influence of magnetism, before coming to the role of God and the importance of scripture in research and more specifically, his model of magnetism.

To Kircher, the magnetic power of God was quite literal. All the elements of the loadstone were reflected in the nature of God and the Trinity. They acted with the attractive, dispositive and connective powers of a loadstone but acted on the soul of a person rather than iron. He believed there was scriptural evidence of this, especially in John 6:4 “no one comes to me unless the one who sent me shall have drawn him.” This was, to Kircher, demonstrable evidence of both the magnetic quality of God’s power and Christ’s knowledge of the true nature of His power as magnetic. God could, as a loadstone could to iron, exercise control and harmony upon his subjects. As His son, Christ was also able to move the hearts of men, in the same way that God worked with the analogy of the loadstone. The Holy spirit had a connective power, which bound subjects before God and Kircher envisioned it as acting similarly to magnetic fields, where the range of its influence was over all of Christendom. Just as the Trinity was the spiritual loadstone, people were the pieces of iron, something under the complete control of the loadstone of God. It was an innate element of human nature, to be drawn towards the divine, a natural appetite and yearning of the spirit. The search and longing for the Godhead was simultaneously an intellectual and spiritual attraction. The mind would unite with the wisdom of God through study and through good work, confession, and purging the soul of sin and uncleanliness God’s blessing could be given. [1]

Kircher’s conceptualization of God was unique among other scholars and Church doctrine. Other scholars had utilized the metaphor of magnetism and divinity before, but none had done so quite as literally as Kircher, or by placing God as the central magnet of the universe. Kircher again stood apart by de-emphasizing Christ and focusing much more on the Holy Spirit, where Jesuits typically emphasized Christ above the Trinity. He also drew from more than just scripture, seeking out hermetic knowledge and Jewish mysticism. It was through these writings that he strengthened his argument of the magnet as the foremost emblem of God’s power and influence over the natural world, his activity in the cosmos. While scripture was the word of God and therefore held the preeminent position as the final arbiter of truth, Kircher regularly sought sources of ancient knowledge and the Hermetic philosophy of a unifying all powerful force behind all of creation resonated with Kircher’s magnetic theory. [2]

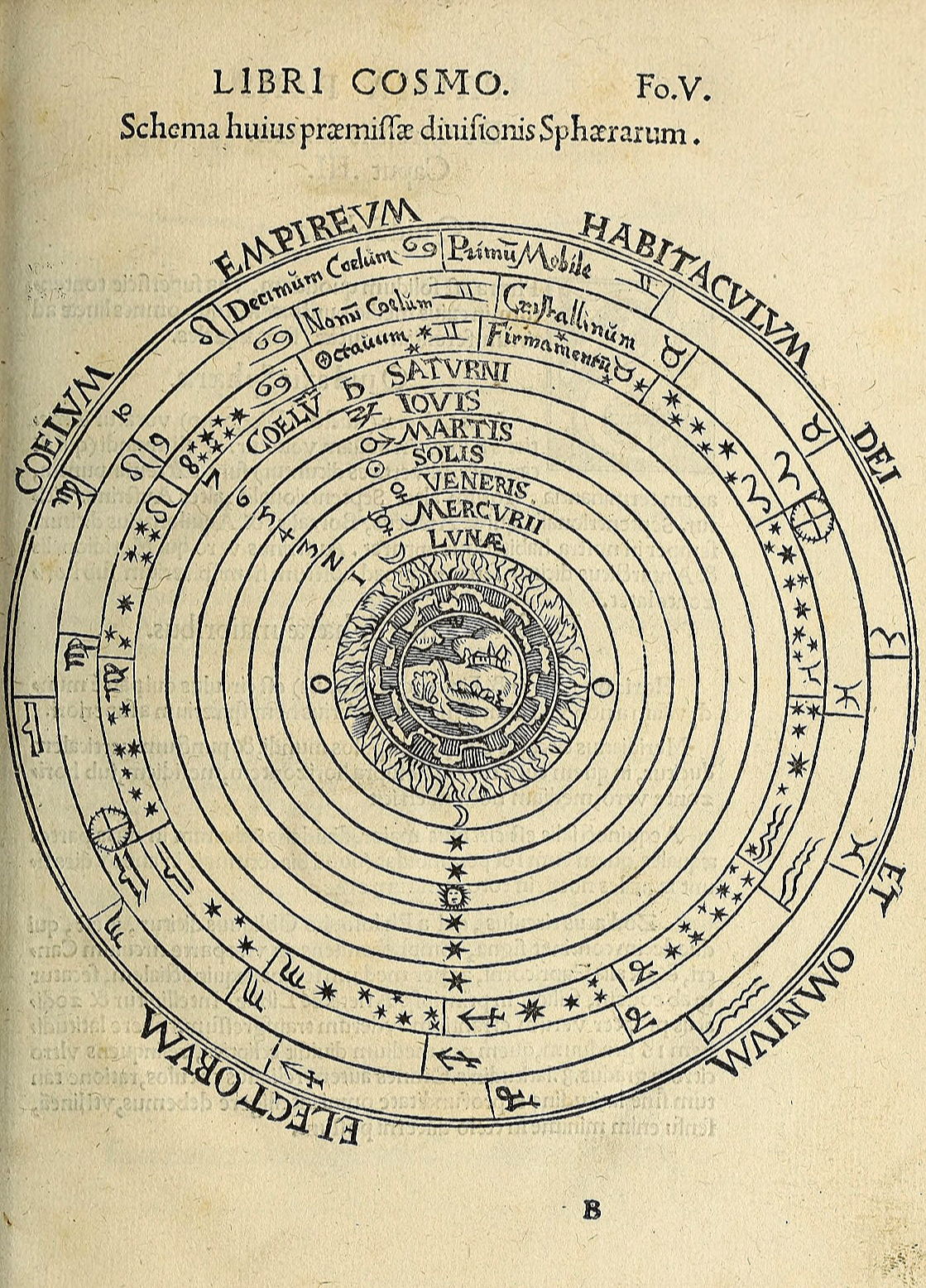

Image source: Peter Apian’s Cosmographia, per Gemmam Phrysium, […] (1539), Internet Archive

For Kircher, the magnet was the ultimate emblem of God’s power and influence over the natural world, the proof of His activity in the cosmos. Kircher wrote of the magnet that it was:

Singulae illud naturae, veram caelorum simiam totius Ideam universae, novorum mundorum reclusorem, divinam quondam ad inexhaustas aorbis terrarium divitias vigulam et clavem, totius Denique naturae compendium

The singular symbol of nature, the true ape of the skies, the idea of the whole universe, the envelope of new worlds, the divining rod and key to the unknown treasures of the earth, the epitome of all nature… [3]

As this epitome of nature, it was the symbol of creational forces, a force which echoed in classical and mystical forces, with the forces of friendship and discord, sympathy and antipathy, concord and dissonance, life and death all being united under the attractive and repulsive abilities of the loadstone. In connecting all these mystical forces to the power and influence of God, by studying the magnet once could unveil natural and divine mysteries; its magnetic force was what connected all of the disparate elements of reality and nature under a single force. This belief of Kircher’s blended into spiritual thinking, where this substance represented the unknown, unseen force behind all things. Kircher’s cosmos was inspired in part by the Neoplatonic idea of the universe as an ordered series of creations, where each level demonstrated a degree of divine wisdom. The magnet operated on all levels, from the mundane to the divine central magnet of God, the force reflecting through all levels of creation in the perfect meld of natural and divine. [4]

The loadstone and the divine were directly and completely interwoven together. In Kircher’s theology, the way through which God and the Trinity acted upon man were magnetic in a true and literal sense. All divine feelings of man were attributable to the magnetic nature of God, where He was the loadstone and mortals were bits of iron. This was a philosophy unique to Kircher, but one that he connected to classical and older natural philosophies. He melded a more modern interest in magnets with older philosophies of Aristotle and Neoplatonics with his own Jesuit beliefs in the natural truth of the Testaments. As the power of the loadstone was the power of God, its abilities were seen and commented on in all realms of the natural world, from the inner workings of the Earth to medicine to the soul. Kircher could see its workings in all levels of the cosmos, where its influence was clear in each level – even while it was not the sole force or action present, it was present, nonetheless. To Kircher, it was the clear symbol of divine action, both through his theological understanding and through his explorations of the natural world.

[1]

Martha R. Baldwin, “Athanasius Kircher and the Magnetic Philosophy” (PhD diss., University of Chicago, 1987), 453-454, 478.

[2]

Ibid., 461-463.

[3]

Athanasius Kircher, Magnes Sive De Arte Magnetica Opus Tripartitum, 3rd ed. (Rome: B. Deversin, 1654), https://archive.org/details/KircherMagnesSive1654, proemium.

[4]

Baldwin, The Magnetic Philosophy, 368, 464-466.